Seeing the universe in an infinity of polka dots

An obsessive Japanese conceptual artist calls the outsider artist label into question, writes Sue Smith

An obsessive Japanese conceptual artist calls the outsider artist label into question, writes Sue Smith

Yayoi Kusama

TATE MODERN, London

Continues until June 5, 2012

PERHAPS one of the most alluring (if illogical) personas attributed to artists is that of the antisocial Outsider – the uneducated, untrained naïf, the tribal artist, the criminal, underprivileged or insane individual, who lives beyond the conventional norms of society and is motivated purely by the joy of making art, untainted by awareness of the art world and the art marketplace.

The Outsider’s art work thrills like no other because the artist’s personal story so often reads like a frog-prince parable (a quest to overcome underprivilege, disability or bad luck) while the work itself acquires an aura of raw, real, powerful and astonishingly originality – firstly, as David Maclagan writes (Outsider Art, p.7), because it seems to have no precedents in the normal art world and secondly because the marginalised creator seems to lack the usual motives for making art (which Freud summed up as ‘fame, money and the love of women’).

The thirst for “authentic” orginality goes back to the post-Renaissance emergence of the artist as an individual expressive figure (unshackled from the medieval craft guild-workshop system) and the 18th century Romantic cult of the artist as a visionary genius, whose extraordinary experiences borders on madness.

True “outsider art” is of course a contradiction, or at the least a shortlived phenomenon, as we have seen ad nauseum since the late 19th century. Damaged outsiders, like Van Gogh and Pollock, are often less innocent outsiders than highly ambitious and calculating if ultimately unlucky insiders. And art movements that began as a radical antithesis to conventional forms of art, such as Pop Art in the 1960s and Australian Aboriginal desert painting in the 1990s, have been quickly assimilated and some would say, quick to acquiesce: collectors and museums acquire it, magazines, exhibitions and books pore over it, prices rocket, and it is finally accepted into the canon of contemporary art.

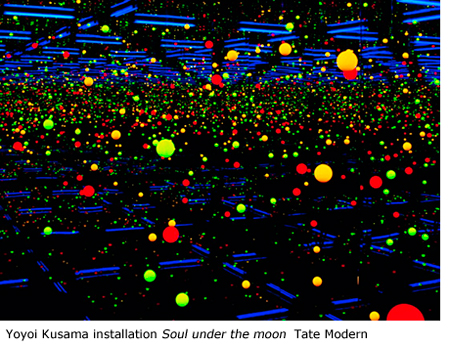

Superficially ticking some of the “outsider” boxes, is the Japanese artist, Yayoi Kusama, known for her obsessive installations of infinitely mirrored polka dots and her voluntary residence in a psychiatric institution.

A spectacular exhibition of this conceptual artist’s work (immersing viewers in her obsessively charged visions of endless nets of dots and infinitely mirrored space) is on view at London’s Tate Modern until June 5, 2012.

Kusama has received extensive press and art world adulation for parlaying her “outsider” identity in many guises – as a woman artist in a male-dominated society, as a Japanese person in the Western art world, and as a victim of her own neurotic and obsessional psychological trauma.

Yet an outsider identity is in some respects an unsatisfactory label for Kusama, born in Matsumoto, Nagana Prefecture, as the fourth child in a prosperous and conservative family – even though she heard voices and saw visions from childhood, including halos around objects and hallucinated net and dot patterns. ‘One day looking at a red-flower-patterned tablecloth on the table,’ she has recalled,’I turned my eyes to the ceiling ans saw the same red-flower pattern everywhere.’

It was a tumultuous childhood: her father was mostly absent and her mother derided Yayoi’s interest in art and her individualism, even going so far as to smear and tear up her daughter’s drawings. Kusama developed psychological disorders that later required psychiatric care and her art has often been explained as a working-out of her childhood neurosis.

It was a tumultuous childhood: her father was mostly absent and her mother derided Yayoi’s interest in art and her individualism, even going so far as to smear and tear up her daughter’s drawings. Kusama developed psychological disorders that later required psychiatric care and her art has often been explained as a working-out of her childhood neurosis.

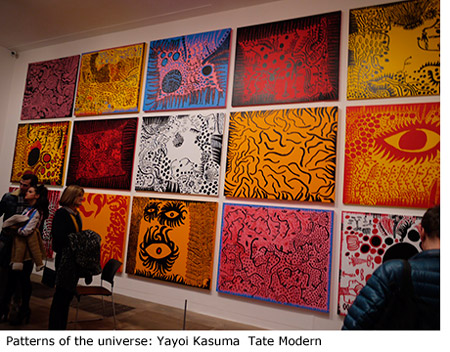

‘I wanted to pursue art to cure my mental illness,” Kusama has said. It has been said that she came to understand enlessly proliferating patterns as an expression of an underlying order to the universe, and she began to draw shapes that resembled cells, mollecules, planets, stars and nets.

But despite her mental instability, Yayoi received a rigorous and highly traditional art training. In 1948, she left home to enter senior class at Kyoto Municipal School of Arts and Crafts, where she studied Nihonga painting, a strictly formalised style developed during the Meiji period. ‘When I think of my life in Kyoto,’ she has been quoted, ‘I feel like vomiting.’ Yet, tellingly, she not only survived the rigidities of this master-disciple system, but even graduated the following year.

At 28, with a few shows in Japan already behind her, the young artist left her home country for the United States. ‘I did not leave Japan, I fled Japan,’ Kasuma has recalled. ‘Labelled as a lunatic, I had been ostracised from art circles.’

Even so, she was savvy enough to write first for help to the high-profile American artist, Georgia O’Keeffe (who responded somewhat frostily: ‘It seems to me very odd that you are so ambitious to show your paintings here, but I wish the best foir you.’). Undaunted, Kusama held her first solo show in Seattle and then arrived in Manhattan in 1958, armed with some 2,000 of her watercolours and drawings.

Quickly assimilating the large-canvas proportions and techniques of the New York School, Kusama within 18 months was exhibiting her first “infinity net” paintings, presenting an all-over, intricately wrought pattern (which have been described as bridging Abstract Expressionism and later Minimalist painting).

Quickly assimilating the large-canvas proportions and techniques of the New York School, Kusama within 18 months was exhibiting her first “infinity net” paintings, presenting an all-over, intricately wrought pattern (which have been described as bridging Abstract Expressionism and later Minimalist painting).

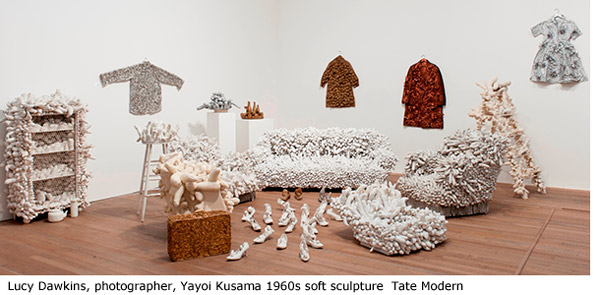

At the centre of the US art world in the 1960s, she came into contact with artists including Donald Judd, Andy Warhol, Joseph Cornell and Claes Oldenburg, influencing many along the way as she developed soft sculptures (armchairs, sofas, tables and even a rowboat) with bulbous, phallic protrusions.

Images from this time often show Kusama posing nude as she achieved fame and notoriety with nude art happenings and events. But while promoting herself at the centre of her art, she also worked tirelessly, sometimes for 50 to 60 hours at a stretch, exhaustingly creating paintings, drawings, collages, experimental films, environmental installations and performance pieces.

Kusama returned to her country of birth in the mid-1970s, drifting into obscurity and becoming a voluntary resident of the Seiwa Hospital for the Mentally Ill in Tokyo, where she still lives. In recent years, interest in her career revived and she is now Japan’s most prominent contemporary artist.

To be sure, Yayoi Kusama’s career has received more than a fillip from promotion of her persona as mentally unstable “outsider”, yet in the end she impresses as an art world “insider”, who flourished despite her disability not because of it. Well-trained, hard-working and well-connected in influential art circles as well as greatly talented, the bedrock of her achievement was persistence and responsiveness to her own times not a borderline flash of genius/madness creativity.

To be sure, Yayoi Kusama’s career has received more than a fillip from promotion of her persona as mentally unstable “outsider”, yet in the end she impresses as an art world “insider”, who flourished despite her disability not because of it. Well-trained, hard-working and well-connected in influential art circles as well as greatly talented, the bedrock of her achievement was persistence and responsiveness to her own times not a borderline flash of genius/madness creativity.

Yet the myth of Yayoi Kusama the outsider persists, because it is a way of believing (as audiences seem to want to be persuaded over and over again) that training, expertise and hard graft somehow will never stack up to the beguiling myth of raw inventive artistry.

Recommended Reading: