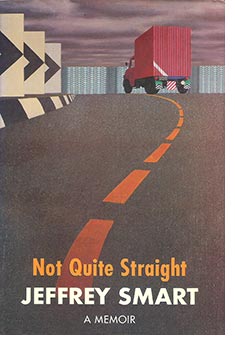

Not Quite Straight - A Memoir

JEFFREY Smart has painted some of the post-1945 era’s most memorably poignant images of urban loneliness; but his own life has been famously sociable.

JEFFREY Smart has painted some of the post-1945 era’s most memorably poignant images of urban loneliness; but his own life has been famously sociable.

Born in Adelaide in 1921, Smart had a glimpse of his destiny early: at the age of four, he was taken on a grand tour of Europe, and he spent much of the next 38 years plotting and planning and desperately saving to go back there permanently. His autobiography, "Not Quite Straight", launched this week, tells, in inimitable style, of his encounters with family, friends, lovers and fans as he achieved his eventual transformation from Adelaide art teacher to suave Tuscan "signore" and successful artist.

Smart’s memoir is a vivid series of snapshots of a life lived out in sometimes seedy, more often exotic and affluent, locales: from working as a sink scrubber on a slow boat to London, to working as Phidias on ABC radio, and to having dinner parties with writers David Malouf and Germaine Greer.

It is an entertaining and gossipy read, giving a shrewd insider’s account of the rarefied artistic and social circles in which Smart moves. Yet there is nothing superficial or pretentious in the way he conveys his feelings. He is frankly honest - and sometimes devastatingly funny - about being dishonest about his homosexuality and impatient with his scatterbrained mother; about being hung-up on surburban notions of comfort and security; and about being bossy and manipulative.

Smart is a dry humourist who is often as merciless to himself as to others. As a 24-year-old art master bent on seducing a willing 15-year-old student, Laurie, he sadly admits his own manipulations: "When I later read "Lolita" by Nabokov I could see my cunning ploys and the ‘so-near-yet-so-far’ torments’ all described." Later, he laments his (partial) duplicity in aiding a feckless lover of Donald Friend’s to decamp. And, when touring the beautiful Greek isles with fellow painter Justin O’Brien, he can see his own prissiness when he orders the "squalidly Irish" O’Brien to take down a clothes line he has put up sullying the peerless view.

The memoir is also fascinating because Jeffrey Smart has been celebrated for his unwillingness to say much to interviewers and writers about his art. This first book by the artist reveals an inner life which could only have been guessed at.

Smart is a practical person and paints with crisp realism, but just as there is poetry beneath the hard bright surfaces of his pictures, so he turns out to be surprisingly fey and suggestible: he is interested in theosophy, attends seances, and believes dreams can sometimes foretell the future (he describes a frightening dream about a car accident, which almost came to pass later, although injury was averted).

Modest about his own painting, but doggedly determined to stick to his own personal realist vision, he is scathing about other artists in the 1950s who, in his view, too eagerly jumped onto the bandwagon of the popular American abstract expressionist movement. "I now think of the abstract expressionist movement as a disaster," he writes, adding sardonically that when in this decade he discovered (hallelujah!) a figurative work in a magazine, he "felt like Noah when the dove came back with an olive branch."

He does not like the sloppiness of some abstraction (although he learned a lot from the clean machine-like forms of Leger, who taught him for a time in Paris), and he sighs noisily through the book at the general lack of interest today in teaching young artists to learn to draw and paint well, through a disciplined academic art training. But he has little interest in theorising about art and inspiration. All he offers by way of explanation is:

"Many of my paintings have their origin in a passing glance. Something I have seen catches my eye, and I cautiously rejoice because it might be the beginning of a painting. Sometimes it is impossible to stop ... and it does happen that when I get back to the place, I wonder what on earth it could have been that enchanted me - it wasn’t there. Enchantment is the word for it."

If Smart is reluctant to pin down his art, the art establishment itself has often been unsure of how to deal with him: he does not fit neatly into the Australian artistic mainstream, and at various times (such as duing the 1950s abstract expressionist craze) he has been ignored by the powerful art institutions. Some of this was evidently wounding: he mentions in passing, for instance, that the Australian National Gallery rarely hangs his work, but he is far too urbane to make heavy weather of such slights.

Still, all in all, it has been a fortunate life, with unflagging aspiration, hard work and talent justly rewarded. At 75, Smart is still producing quality work which can fetch $100,000 or more, and this eagerly awaited memoir has been launched at one of the sanctum sanctorums, the Art Gallery of New South Wales. At the end of the book, we leave him hoping that he may, like Titian, be lucky enough to paint until he is 98. Jeffrey Smart is lucky.

Copyright © 1996 Sue Smith. Not to be used without permission of the author.