Classic Cezanne

"Classic Cezanne" The art of Paul Cezanne

Art Gallery of NSW

Sydney, New South Wales, Australia 1998

Review by Grafico Topico's SUE SMITH

An edited version of this review was first published in The Courier-Mail - 12 December 1998

UNBELIEVABLE is the word Art Gallery of New South Wales curator Terence Maloon uses to describe his all-consuming three-year involvement in curating Australia's first major exhibition of the great modern master, Paul Cezanne.

UNBELIEVABLE is the word Art Gallery of New South Wales curator Terence Maloon uses to describe his all-consuming three-year involvement in curating Australia's first major exhibition of the great modern master, Paul Cezanne.

The Cezanne show -- insured for a sum greater than the Sydney gallery's building and all the art works inside it -- has been, as Maloon says, the most ambitious and expensive project the gallery has ever undertaken: "It's one of those unbelievable things: you step into the project and eventually step out -- but in the meantime, your life has changed. For me, it's been three years of total immersion in an exhibition that's also been a real watershed experience for this gallery: we now have the infrastructure here to put together a great show like this, and it has only happened through tremendous teamwork."

But while cohesive effort pulls great shows together, in the first place the big challenge for Australian galleries doing such exhibitions is to persuade overseas lenders to part with their astronomically valuable pictures. Asking for loans is, says Maloon, who tripped around the world with his personable director, Edmund Capon, an intimidating process of "barging into meetings with museum directors who are total strangers and quite sceptical."

The major selling point, he adds, is to have a strong and different exhibition concept and the involvement of leading scholars, such as distinguished Cezanne experts, Richard Shiff and Walter Feilchenfeldt, who worked as consultants for Sydney. Lenders are also reassured by Australia's excellent track record with earlier shows like Canberra's admired 1996 Turner exhibition. But other factors do come into play: some museums who lent Cezannes to the blockbuster 1996 Cezanne show (in Paris, London and Philadelphia) now want to rest their works for a few years, and then there are geopolitical considerations, and loan fatigue from major institutions tired of being besieged for their pictures.

"So much has been written about artists like Cezanne already, that you need to come up with something quite significantly different that will enhance the lender's works -- which we were able to do," explains Maloon.

"So much has been written about artists like Cezanne already, that you need to come up with something quite significantly different that will enhance the lender's works -- which we were able to do," explains Maloon.

"The Turner show was great for Australia: people (in overseas museums) felt it was a succinct, scholarly show put together with love; it was a benchmark. But we've had a phase of too many museums converging on (New York's) Museum of Modern Art, who've said, `We're putting an embargo on loans to Australia for the next 10 years -- we can't have our permanent collection being continually stripped for loans'.

"And it's all very geopolitical: we do well (asking for loans) in the States and France, for example, but badly in Germany and Scandinavia -- Australia's just not in their minds."

In the end, Sydney has managed to borrow 30 paintings -- two of which were owned by Cezanne's contemporary, Monet, and including five (of only 13 in Cezanne's entire output) which were signed by the artist and therefore considered to be "finished" (a contentious issue in Cezanne studies) -- and 52 watercolours and drawings. "It is a first-rate selection of the paintings," says Maloon, "and as fabulous a collection of his watercolours and drawings as you would want to see."

In recent years there have been exhibitions of Cezanne's early and late work, and the 1996 blockbuster presenting a narrative of his entire career. But Sydney's show, which is a vivid and compelling display spread throughout seven galleries, is the first to concentrate on Cezannes' "mature work" from the 1880s to his death in 1906 (with, as well, a fine earlier group of his 1870s landscapes, a self-portrait and works on paper to show his Impressionist origins).

The exhibit is keen to make new points about Cezanne as a "classic" artist pursuing an art of order and structure; and as a "painter's painter", for whom the inventive process was everything and which varied according to what he was painting. To demonstrate Cezanne's shifting and "improvisational" mindset, Maloon has divided the show into thematic groups, showing the transition from Impressionist to classicist; still lifes; volumes & planes (showing the artist solving pictorial problems); Provencal landscapes; portraits; bathers & nudes; and sous-bois (undergrowth) landscapes.

B ut what makes this exhibition really remarkable is that it is the first to argue that Cezanne's sous-bois landscapes -- allover, abstracted compositions of interwoven trees and vegetation -- were his most original contribution to modern landscape painting, anticipating the later developments of Matisse, Picasso, Braque, Mondrian and Jackson Pollock. Supporting this argument, a parallel show in the gallery, `Australian painters seeing Cezanne' demonstrates how painters like Grace Cossington Smith, John Passmore and Fred Williams also further developed Cezanne's sous-bois and other stylistic innovations.

ut what makes this exhibition really remarkable is that it is the first to argue that Cezanne's sous-bois landscapes -- allover, abstracted compositions of interwoven trees and vegetation -- were his most original contribution to modern landscape painting, anticipating the later developments of Matisse, Picasso, Braque, Mondrian and Jackson Pollock. Supporting this argument, a parallel show in the gallery, `Australian painters seeing Cezanne' demonstrates how painters like Grace Cossington Smith, John Passmore and Fred Williams also further developed Cezanne's sous-bois and other stylistic innovations.

The life of Paul Cezanne has sometimes been written about as a kind of apotheosis of the romantic 19th-century image of the artist as outsider -- centering on Cezanne's supposed Southern peasant uncouthness, early tumultuous sexual fantasies and later fear of women, but also embracing his holy sage status in old age.

But this exhibition concentrates instead on the artist's keen analytical mind, with the result that Cezanne tends to remain both awesome and aloof. Even in his 1880-81 `Self portrait' he doesn't let his defences slip, but treats us instead to a fiercely concentrated, side-long stare, painting his own face with the same impersonal interest he gives to the background wallpaper. The closest he comes to displays of affection is in a tender 1882 pencil drawing of his son; the greatest hint of passion is in Canberra's odd and erotic little painting after Delacroix, `Afternoon in Naples', c.1875; and the nearest thing to humour is the way he visually rhymes his bald, domed head with an apple in another 1880-84 drawing, `Self portrait with apple'.

There is, surely, something a bit strange about a man who paints his wife as though she were as monumental and distant to him as the far-off peak of Mont Sainte-Victoire. Madame Cezanne in her two portraits in the show is a figure of impressive, Sphinx-like gravitas, her inscrutable, obsidian eyes staring out of an oval head that recalls the later stone sculpture of Brancusi.

Cezanne was notoriously shy of society, paranoid about interlopers like Gauguin who tried to "steal" what he described as his "petite sensation": the suddenness of seeing the world around him."I should remain alone," he said. "People's cunning is such that I can't get away from it, it's theft, conceit, infatuation, rape, seizure of your production, and yet nature is very beautiful."

Nature, in the northern French and Provencal landscapes here, is indeed very beautiful. And Cezanne's feelings before it were strong, even rapturous. We become aware of this before the extraordinary sous-bois paintings of the dense forest around Aix, where he doesn't simply paint trees, branches, leaves, rocks, but captures the way light hits them and records the vibrations of colour and air between them.

But while he was acutely sensitive to the minutest variations in his favourite landscapes, Cezanne's paintings are also records of the act of painting itself: of its mistakes and corrections, hesitations and deliberations. This emphasis on process also reveals itself in untouched places on his canvases, which may be there quite deliberately (as in the watercolours) to aerate the surface and signal the dynamic evolution of the composition, yet in the most extreme examples, the bare patches also lead to questions of whether the paintings were incomplete or abandoned.

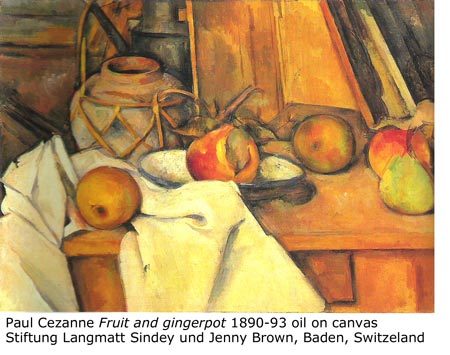

Observing such things, viewers may gradually become slightly mesmerised by the artist's unstable, shifting process of looking and painting. We start to notice in a splendid series of still lifes, for example, the way light always falls arbitrarily on things, how the corners of tables fail to properly align, plates are imperfectly joined ellipses, baskets are too big for the tables they sit on, and apples crowd on plates too small to hold them. Yet -- hey, presto! -- these are absolutely convincing images of volume and power, organised often in dynamic spiralling arrangements, as Terence Maloon notes, like "a galaxy of objects" revolving around a sun.

Observing such things, viewers may gradually become slightly mesmerised by the artist's unstable, shifting process of looking and painting. We start to notice in a splendid series of still lifes, for example, the way light always falls arbitrarily on things, how the corners of tables fail to properly align, plates are imperfectly joined ellipses, baskets are too big for the tables they sit on, and apples crowd on plates too small to hold them. Yet -- hey, presto! -- these are absolutely convincing images of volume and power, organised often in dynamic spiralling arrangements, as Terence Maloon notes, like "a galaxy of objects" revolving around a sun.

Cezanne's lesson in such works is this: nature and the quotidian everyday world provide him with his motifs, but he is always, as he told younger artists, the master of his subjects. He is the first great modern artist because he understood that the painter's major task is to record the subjectivity of his own visions, and that a painting before it is anything else is an arrangement of colours on a flat surface.

We may never quite understand what makes this most impersonal of artists tick, but casting aside such vain regrets, there are worse fates than peering into these vivid rectangles where women turn to stone, apples revolve like planets and colour is always vibrating in the summer air.

`Classic Cezanne', Art Gallery of New South Wales, Art Gallery Road, The Domain, Sydney, until February 28, 1999.

Copyright © 1998 Sue Smith. Not to be used without the permission of the author

Recommended reading: