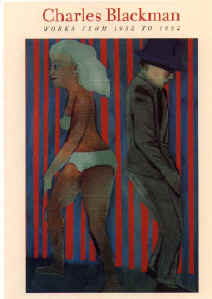

Charles Blackman

Charles Blackman

Works from 1952 to 1992

Philip Bacon Galleries 1999

Brisbane, Queensland, Australia

Review by Grafico Topico's SUE SMITH

This review was first published in The Courier-Mail , Brisbane, Australia - Saturday, 6 March 1999.

NIGHT falls in London, descending on children in a playground. Under flowering shrubs, cats sit like Egyptian sphinxes and watch the world go by. Inside the shadowy houses, lovers kiss hungrily, two heads merging as one amoeba. Over there is Barry Humphries, and some unknown poet, and also a strange, green-eyed geisha, all fixing us in their gaze. And into the night, a schoolgirl scuttles -- she's late, so late -- but somewhere a sinister figure waits, biding his time in the shadows.

NIGHT falls in London, descending on children in a playground. Under flowering shrubs, cats sit like Egyptian sphinxes and watch the world go by. Inside the shadowy houses, lovers kiss hungrily, two heads merging as one amoeba. Over there is Barry Humphries, and some unknown poet, and also a strange, green-eyed geisha, all fixing us in their gaze. And into the night, a schoolgirl scuttles -- she's late, so late -- but somewhere a sinister figure waits, biding his time in the shadows.

These are some of the stars of the Charles Blackman show, a survey of almost 50 paintings and drawings at Brisbane's Philip Bacon Galleries, covering the celebrated painter's career from 1952 to 1995.

It's an exhibition that's no doubt been eagerly awaited by Queensland viewers, though it's one of several survey shows of Blackman's work to have been assembled in recent years, from exhibits held in commercial galleries to the large touring 1993 retrospective shown in Melbourne, Brisbane and Perth.

But no matter how often his work is seen, Blackman is one of those artists whose work remains compelling for a large audience. Like Nolan's Ned Kelly, like a fractured Picasso woman or a Dali melting watch, Blackman's Alices, schoolgirls and lovers have become fixtures in the modern imagination. For many, his work stands for the remembrance of lost childhood, and gives form to the strange world of dreams.

But when people respond to Blackman as a kind of sweet romantic, as decorative escapism, they miss his true strength. It is when he paints what we felt all along, but didn't have a name for -- or only dared to confront in our dreams -- that we truly recognise ourselves and our experience.

Sweetness doesn't come into it, says Blackman, on the phone from Sydney. At 70, and after a recent stroke, he is now frail and spends less time in front of his easel. But he is still as witty and acute in his observations as ever, and keen to discuss his work and such imponderables as the meaning of dreams. The latter he considers to be a kind of "paradigm" of reality, simply waiting to be enacted. "I am a romantic painter, (but not sweet) -- oh no. That's wrong. Dreams are what you're made of, and very often nightmares, too. A dream is quintessentially a reality when it is fulfilled."

One of the dreams Blackman's work often focuses on is the "lost domain" of childhood. His paintings provide us, however, with both the charm of children at play, and with the shock, the frisson, of a child's aloneness and vulnerability. This is Blackman's power and the key to his popularity. His images are both accessible and strange: Blackman hands poignancy and an enigma to us, along with the vivid bunch of flowers in a child's hand.

Blackman's own childhood in Depression days Sydney was difficult. His father deserted the family when Blackman was four; his mother was pretty, vivacious, and a compulsive gambler. She worked long hours as a waitress and cleaner to keep Charles and his three sisters, sometimes placing them in homes when she could not cope. At 13, Blackman left school to help support the family by working as a newspaper copy boy.

It was a hard upbringing and one that perhaps gave him a profound insight into the feminine mind. But the thrice-married artist, who seems most at ease painting feminine subjects (schoolgirls, Alice in Wonderland, Zelda Fitzgerald), demurs at the suggestion that his life has been shaped by women. "Well, the women have likely been shaped by me just as much," he ripostes, but relenting, adds: "I suppose you could say they have influenced me very much as a person. From my experience there is very much a female sensibility."

It was a hard upbringing and one that perhaps gave him a profound insight into the feminine mind. But the thrice-married artist, who seems most at ease painting feminine subjects (schoolgirls, Alice in Wonderland, Zelda Fitzgerald), demurs at the suggestion that his life has been shaped by women. "Well, the women have likely been shaped by me just as much," he ripostes, but relenting, adds: "I suppose you could say they have influenced me very much as a person. From my experience there is very much a female sensibility."

Still, though the feminine anima makes up an important part of Blackman's creativity, now, when Blackman looks back, he nominates friendship as the most important thing in his experience, "the everlasting truth of life".

Many of his friendships with fellow painters -- Arthur Boyd, Albert Tucker, Sidney Nolan -- are well known. But perhaps most crucial for the development of Blackman's art were the friendships he struck up with poets and writers who introduced him to the world of literature. In 1947, there was the New Zealand poet, Lois Hunter, who led Blackman to Rimbaud, Baudelaire and T.S. Eliot. In the mid-1950s, Blackman's acclaimed series of Alice paintings came about after listening to the classic Lewis Carroll book in taped form with his sight-impaired writer wife, Barbara. Later, too, there were fruitful book collaborations with writers Al Alvarez and Nadine Amadio, who wrote the words to Blackman's rainforest and Paris paintings.

"Not many painters are literary-minded," Blackman observes. " They paint what they see, or what they feel. But I read a lot and I try to make the image evocative of the books that I've read.'

Yet, as important as his literary contacts have been, this is not to say that Blackman is an artist who simply illustrates what he reads, far from it. Alice, in his paintings, for instance, lingers and grows in the mind, becoming an awkward child-woman or an alter-ego for Blackman himself -- and not just a character from a favourite children's story.

Literature can provide a starting point, but, as he says, the route to the final image is often long and mysterious. " With drawing, you can do image after image, fairly rapidly. But painting takes a lot longer; it can take hours to contemplate what you're doing, and sometimes it takes a very long time to do the (actual) painting." And, at the end of the day, the painting must work as an image that stands alone. How does Blackman avoid doing mere illustrations of the stories he reads? "You illustrate them with magic," he replies emphatically."If you bring that magic to life, well, you bring the reality of the poem or the drawing to life, too."

Charles Blackman', Philip Bacon Galleries until March 31, 1999

Copyright © 1999 Sue Smith. Not to be used without the permission of the author

Recommended reading: