Arthur Boyd

Arthur Boyd 1920 - 1999

An Obituary

by Grafico Topico's SUE SMITH

An edited version of this article was first published in The Courier-Mail, Brisbane, Australia - Tuesday, April 27 1999.

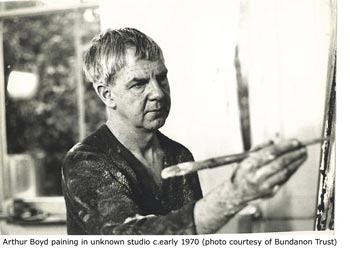

THE hands are stilled. In life they were large, capable, blunt-fingered; a craftsman's paws. He liked to touch the paint, using his hands and fingers to push and pull the oily medium like a potter moulding clay. Galleries sometimes were concerned that the lumps of paint sticking out from his canvases would be damaged by visitors touching them, but he wanted to share his passion for painting, his compassion for humanity. "Let them touch the paintings," he ordered. He hated to be called an artist, that "phoney, romantic" description, saying instead he was "a painter, a tradesman".

THE hands are stilled. In life they were large, capable, blunt-fingered; a craftsman's paws. He liked to touch the paint, using his hands and fingers to push and pull the oily medium like a potter moulding clay. Galleries sometimes were concerned that the lumps of paint sticking out from his canvases would be damaged by visitors touching them, but he wanted to share his passion for painting, his compassion for humanity. "Let them touch the paintings," he ordered. He hated to be called an artist, that "phoney, romantic" description, saying instead he was "a painter, a tradesman".

Arthur Boyd, the celebrated Australian artist, has died at the age of 78. He passed away surrounded by his family at the Mercy Hospital in Melbourne on Saturday, after an illness of three months. He was a man for all seasons. A painter's painter, whose themes of loss and vulnerability -- cripples, Biblical misfits, outcast lovers, wounded soldiers -- intrigued scholars with their complexity, but also touched the widest audience. A successful man, feted by society and showered with honours, who gave away many of his works, and a property valued at $20 million, to the nation.

"Few Australian artists have cast their vision across so broad a landscape of ideas and traditions, both real and mythological, as Arthur Boyd, and few have sustained their creative powers with such force and energy," the director of the Art Gallery of NSW, Edmund Capon, wrote in the foreword to the 1994 Boyd retrospective.

The curator of that touring exhibition, Barry Pearce, writing in the same catalogue, wrote: "Unlike his contemporary Sidney Nolan, who from the outset propelled Australian art into an almost elusive realm of originality, Boyd stood in the river of European tradition, took from it what he needed, and then proceeded to give back something of his own."

The curator of that touring exhibition, Barry Pearce, writing in the same catalogue, wrote: "Unlike his contemporary Sidney Nolan, who from the outset propelled Australian art into an almost elusive realm of originality, Boyd stood in the river of European tradition, took from it what he needed, and then proceeded to give back something of his own."

Born at Murrumbeena, Victoria in 1920, Arthur Boyd was the son of Merric and Doris Boyd, potters and painters, and the brother of painter David and sculptor Guy. The garden and the children ran wild in this bohemian family of artists, and Boyd's unworldly father awakened his social conscience, teaching him "this idea of not hurting any living creature". It was an encouraging atmosphere for a young artist, but the family had its troubles. When Boyd was six years old, his father's pottery studio was completely destroyed by fire, a disaster that financially ruined them. Then, after the birth of their fifth child, Mary, Doris was warned that another pregnancy would endanger her life, and from that moment she abstained from sexual intimacy with her husband. The slow recovery of the pottery after the fire, combined with tension between the parents (heightened by Merric's epileptic fits) affected the young Arthur deeply.

It was his father, this gentle but damaged human, who would ultimately become the Ur-figure for many of Boyd's later paintings of suffering or flawed messiah figures: cataleptic bodies prostrate in death; resurrected beings wafting in the smoke of factory chimneys; the miserable Bebuchadnezzar suffering in the wilderness; and a triumphant Moses leading his people out of the Australian wilderness.

Boyd left school at 14 and spent several years living on Victoria's Mornington Peninsula with his grandfather, the landscape painter Arthur Merric Boyd, who nurtured his talent. One of the happiest times of his life, Boyd's early landscape paintings from this period were simple, drenched in light, and presented an idyllic vision of humanity in harmony with nature.

Before living with his grandfather, he had briefly attended night classes at Melbourne's National Gallery School, but a stronger influence was the Jewish immigrant artist Yosl Bergner, who introduced Boyd to such writers as Dostoyevsky and Kafka. Bergner's profound commitment to humanitarian values reinforced Boyd's social conscience. Some of the paintings of 1938 and 1939 showed the new direction of Boyd's art: the dark backgrounds shrouding heavily outlined heads distorted by anxiety or cruelty, or some other existential turbulence from deep within the individual.

Conscripted in 1941, the war was a decisive event Boyd, reinforcing his concern over many of the phantoms of the 20th century: violence, racism, alienation and isolation. His expressionistic wartime paintings, with their images of cripples and those deemed unfit for war service, were painful images of the dispossessed and the outcast. Two of these paintings established his reputation: `The mockers' and `The mourners' of 1945 used biblical subjects as an outcry against the concentration camps of World War II. Today, they remain wonderfully vehement pictures, their heartfelt anguish all the stronger for the awkward clumsiness of Boyd's figure drawing.

Having served with the Melbourne Cartographic Unit until 1944, after the war Boyd founded a workshop at Murrumbeena with John Perceval, where he turned his hand to pottery, ceramic painting and sculpture. In the 1940s Boyd also had frequent contact with the circle of artists (including Sidney Nolan and Albert Tucker) surrounding John and Sunday Reed at Heide. However, he held himself a little aloof from Heide's hothouse emotional atmosphere, where Nolan and Sunday were lovers under John Reid's nose, and the Reeds adopted Tucker's abandoned son. "(At Heide) you could get eaten up and I didn't like that," Boyd recalled."You could be absorbed into a world in which you would be too inhibited to break out of (and) I didn't need the stimulation of the emotional involvement."

After the war Boyd turned to the Australian landscape, travelling to Victoria's Wimmera country and central Australia, where his distress at seeing "Aborigines in such a bad state" at Alice Springs in 1951 resulted in the compelling Love, Marriage and Death of a Half-caste series (the Bride series) of the late 1950s. He later said: "I'd like to feel that through my work there is a possibility of making a contribution to a social progression or elightenment".

The Bride series launched Boyd onto the international stage, and after participating in the 1959 Antipodean Manifesto exhibition, he left Melbourne for England where he lived for 11 years with his wife Yvonne, and children, Polly, Jamie and Lucy (all of whom became painters). Like Sidney Nolan, he was praised by London critics. Commissions for ballet and opera set designs followed, and, after taking up etching and returning to ceramic painting, he began the Nebuchadnezzar series in response to the Vietnam War.

Boyd visited Australia several times during the early 1970s, and in 1975 gave to the National Gallery of Australia a large number of paintings, drawings, prints and ceramics, representing the bulk of what he still retained of his own work. Also at the beginning of this decade, he rediscovered the Australian landscape, often setting within it anguished figures which allowed him to examine the myth of the romantic artist and the vanities and demands of public success. These included images of the artist naked in austere landscapes, chained to a tree, brushes in one hand, a pile of coins in the other -- images which were received with shock by critics. There was heroism in Boyd's self-exposure in these years, particularly as it was then considered outmodish to be a figurative painter.

Not dissimilarly, the Australian Scapegoat paintings from the 1980s employed the landscape to explore constructions of national identity and the obscenity of war. These were angry canvases, expressing notions of senseless barbarity and the ritual of atoning to angry gods through sacrifice. Boyd later said of this series: "It was the poor that were being punished for no crime of their own. There is only one thing armies are for and that's to kill. It's no good saying they're there to protect you and all that stuff. They're there to actually kill someone. So it's the bloke who does the killing that is the scapegoat."

Not dissimilarly, the Australian Scapegoat paintings from the 1980s employed the landscape to explore constructions of national identity and the obscenity of war. These were angry canvases, expressing notions of senseless barbarity and the ritual of atoning to angry gods through sacrifice. Boyd later said of this series: "It was the poor that were being punished for no crime of their own. There is only one thing armies are for and that's to kill. It's no good saying they're there to protect you and all that stuff. They're there to actually kill someone. So it's the bloke who does the killing that is the scapegoat."

In such later works Boyd became more technically accomplished in his painting than in his earlier work. Nevertheless, his most telling images generally always reassert the basic freedom of painting and humanity's capacity to endure, however occasionally self-deluded we may be.

Many of his 1980s landscape pictures were painted on the Shoalhaven River, NSW, where Boyd bought a property, Bundanon, and returned to live in the mid-1980s. In 1993 the Australian Government accepted the gift of Bundanon, valued at the time at $20 million. It was Boyd's hope that the natural beauty of this place would be preserved for the inspiration of future generations, and he lived long enough to see many young artists enjoying temporary residencies there.

Copyright © 1999 Sue Smith. Not to be used without the permission of the author

Recommended reading: